The Papyrus of Ani was created in Egypt about 1250 B.C. It represents the best preserved, longest, most ornate, and beautifully executed example of the form of mortuary text known as The Egyptian Book of the Dead.

Ani was an important Temple scribe. He and his wife Tutu chose from among some 200 available prayers, hymns, spells, and ritual texts the 80 that most appealed to them. Their completed scroll measured some 78 feet long by 15 inches in height. Their likenesses were painted among the elaborately crafted hieroglyphic vignettes. This individualized papyrus roll would be buried with them, with the intention of opening a gateway in the afterlife. If successful in persevering through the trials they encountered there, they would be free to eventually feast and dally with the gods.

As a magical, polytheistic religion, the Egyptian faith was alive with creativity and energy. It involved a continuous interaction between the individual and the various deities who constituted its elaborate and exalted pantheon. The dignity afforded the observant Egyptian was an invigorating state. One who had led an upright moral life, had shown respect to the gods, and been strong enough to proceed through the dangers and trials of the afterlife, was invited to join the gods—playing board games in beautiful fields, drinking beer, eating, even making love. The successful adherent would reach a stellar glory of his own, at last a member of that hierarchy he had honored throughout his life.

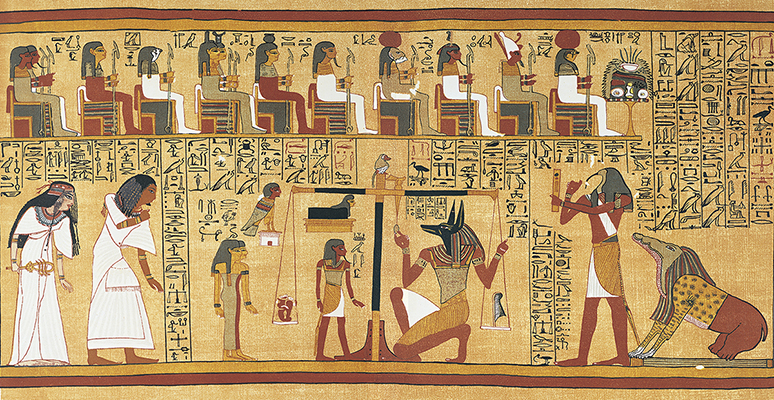

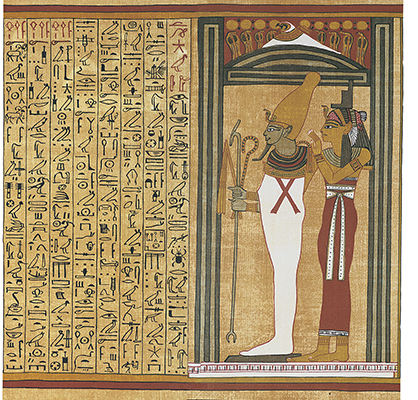

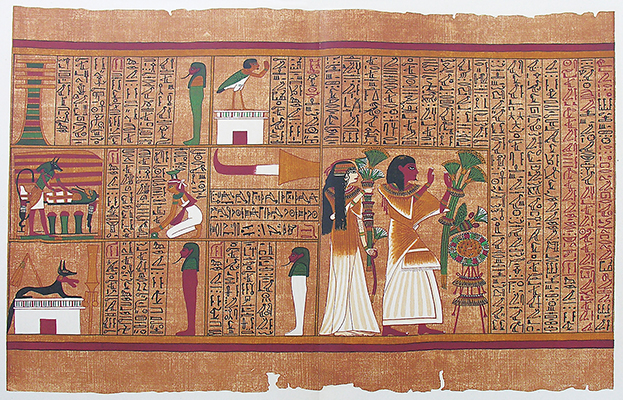

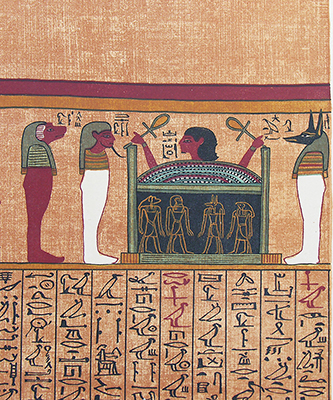

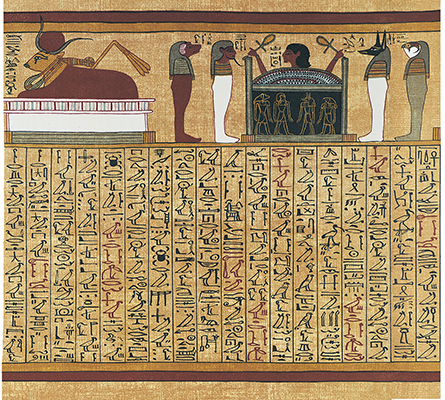

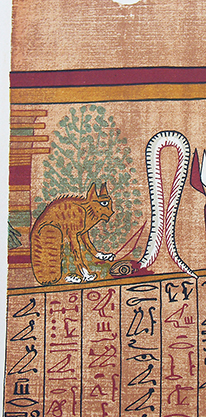

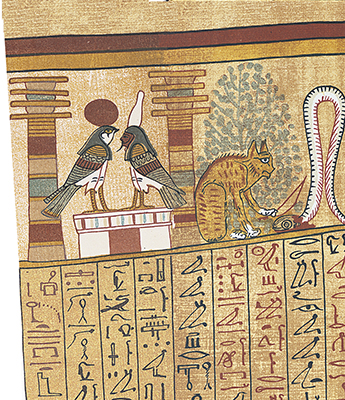

The prayers of The Egyptian Book of the Dead are connected to certain archetypal images. Thus an invocation to Osiris, the Lord of the Underworld, will be written within a painting (or vignette) of that deity. The meaning of the scene is a marriage of word and image, reaching well beyond the merely verbal level of comprehension. One of the best known examples is the Weighing of the Heart scene below. The heart (the moral integrity of the deceased, his conscience) is weighed against the feather of Truth and Justice. If the cumulative effects of a person’s life have allowed his soul to be as light as the feather of Truth, he or she is judged pure and allowed to continue on with the journey. However, if the person’s heart is weighted down with the burden of sin, his soul is flung to the great monster who awaits the recording of the verdict and is no more.

Plate 3: The Weighing of the Heart. (As restored © 1994, 1998 James Wasserman)

In 1888, Ani’s papyrus was acquired by Sir E.A. Wallis-Budge, assistant Keeper of the Egyptian Collection at the British Museum and author of numerous books on ancient Near Eastern civilizations. He described the Papyrus as the largest he had ever seen. “… I was amazed at the beauty and freshness of the colours of the human figures and animals, which in the dim light of the candles and heated air of the tomb, seemed to be alive.” Budge recognized the Papyrus of Ani was the greatest of such scrolls ever found.

When he returned to the British Museum, he made two tragic errors. First, he cut the papyrus into thirty-seven relatively even-length sheets for ease of handling. This “yardstick” method of cutting caused irreparable damage to the continuity of the papyrus. Budge’s translation, released five years later, revealed that chapters and images were often cut in mid-sentence, while carefully crafted images were split onto different sheets. Secondly, he glued the sheets to wooden boards for translation and display. The glue began to damage the delicate sheets, as did their exposure to direct sunlight from a skylight above. (Modern manuscript conservation techniques were unknown at this time and Ani’s papyrus is only one of many damaged in the early days of museum Egyptology.)

Fortunately, Budge also commissioned the elaborate color facsimile lithograph edition of 1890 that I was to discover nearly a century later. (While many modern Egyptologists condemn Budge for a variety of reasons, they all stand on his shoulders. He made these catastrophic mistakes in his quest to share this ancient treasure with the world. Yet, he also left us the tools to reclaim the Papyrus.) Budge’s “elephant folio” (14 x 21 inches) facsimile of the Papyrus of Ani, published by the British Museum, is a magnificent volume. The edition contained no translation, simply presenting a color-lithographed facsimile of the sheets of the Papyrus.

In 1895, the translation of the Papyrus was published. (That translation is reproduced in the ubiquitous but virtually unreadable Dover paperback reprint, the text of which now appears all over the internet.) Most people do not realize that the translation was intended as a companion to the 1890 facsimile. The reader was expected to read the translation, while looking at the pictures of the scroll in the facsimile.

The goal for Studio 31 was to present the Papyrus in an uncluttered manner so that the non-specialist could directly experience its magic and splendor, while maintaining the integrity a specialist would expect. I sought to allow the reader a meditative experience through word and image.

In 1991, after a dozen years of unsuccessfully attempting to get this project published, I teamed up with Bill Corsa of Specialty Book Marketing. Bill was able to sell the project to Caroline Herter of Chronicle Books. The book was first published in 1994. In 2012, Intrinsic Books delivered our tenth printing.

* * * * *

The design challenges of presenting a scroll in book form were complex because a scroll is vastly different than a book. I wanted to maintain the integrity of the images. The production process included making a full-size tracing of Budge’s facsimile—all 78 feet, laid out on the floor and reworked constantly—until we were convinced we had done the best job possible of presenting the scroll as a book. An uncluttered translation was presented below each plate. We essentially combined one book of pictures along the top with another book of words below it. Thus an unusual trim size was indicated.

Budge’s meticulous transcription of the hieroglyphs allowed me to understand some of the problems he had created by his unfortunate cutting of the Papyrus before the translation was complete. For example: On Sheet 3—which shows the famous Weighing of the Heart scene—Budge cut the Papyrus to include the first column of text properly associated with the vignette on Sheet 4. We moved that column to its correct position using Photoshop.

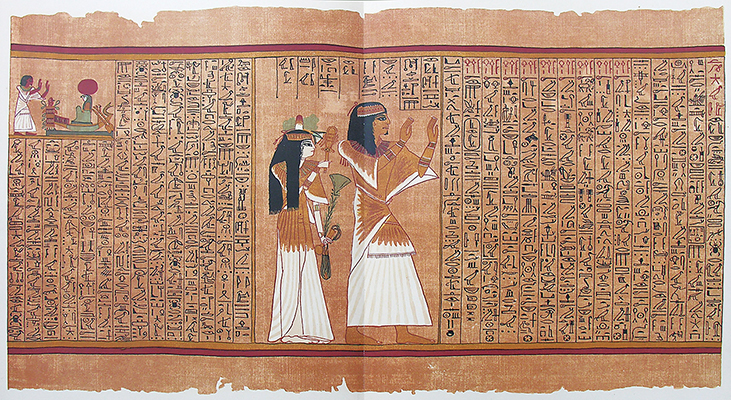

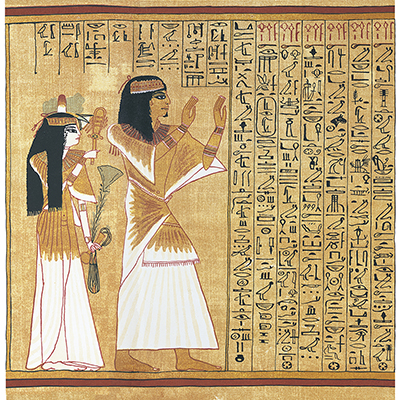

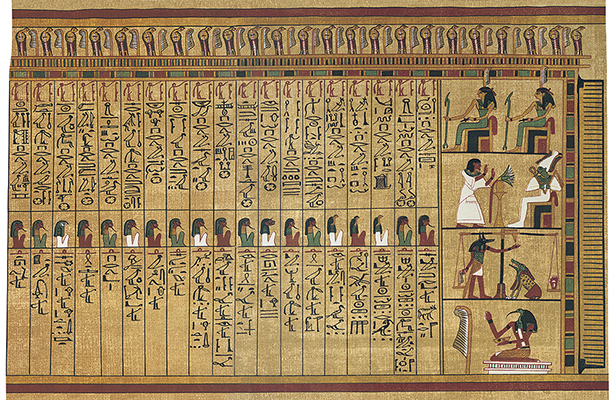

While that was a minor repair, some of the other problems we solved are jaw-droppingly dramatic—such as our modern Plate 19. When Budge cut the Papyrus, his original Sheet 19 (below) shows Ani and Tutu in the middle of the sheet with their hands raised in praise. The texts of the Address to Osiris and Hymn to Osiris are shown at their right.

Sheet 19 of the Papyrus of Ani as cut by Budge (Facsimile Lithograph).

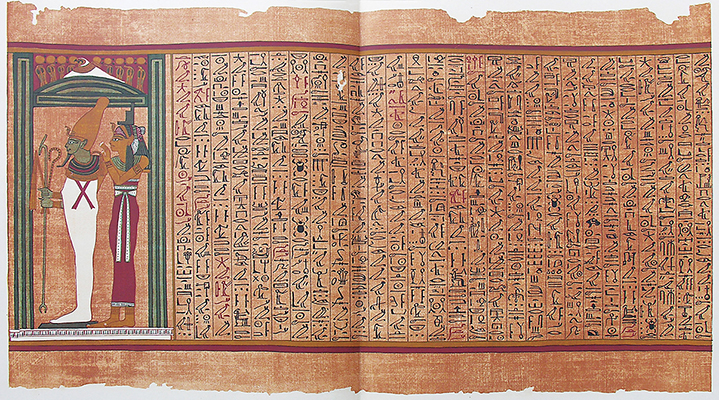

On Sheet 20 of Budge’s Facsimile (below), Isis and Osiris are hanging at the extreme left of the sheet, seemingly an afterthought. The balance of Sheet 20 to the right of their image is a long Sun Hymn. (The Sun Hymn is now reproduced as Plate 20 of our edition of the Papyrus.)

Sheet 20 of the Papyrus of Ani as cut by Budge (Facsimile Lithograph).

I recut the Papyrus to allow Plate 19 to begin with the vignette of Ani and Tutu on the left in their gesture of praise. The text of their Address and Hymn fills the middle of the spread. And on the right side stand Isis and Osiris, the objects of their prayers.

Plate 19: Praise of Osiris. (As restored © 1994, 1998 James Wasserman)

The sole purpose of our extensive electronic retouching was to bring the images closer to their original form—to recreate the original Papyrus of Ani in book form three and a half millennia after the scroll was first painted. We have literally spanned the ages by making use of state-of-the-art electronic technology to reclaim one of the most beautiful handmade treasures of antiquity.

In his Commentary to the book, Dr. Ogden Goelet of New York University describes the importance of the images in The Book of the Dead:

“Over the centuries the visual predominance of image above text continued to grow until, during the final stages of the Book of the Dead’s development, the scribes used only as much text as could fit into the ever-diminishing space beneath the vignettes. The text of a chapter might halt abruptly in mid-phrase or mid-word…. The displacement of text and image is an important phenomenon which should not simply be ascribed to careless work … [the] displacements indicate that the vignettes alone evoked the chapter’s entire religious and ritual content; the images had an innate potency greater than the power of the text accompanying them.”

In fact, it is precisely the “innate potency” of the images of the Papyrus of Ani that our edition is committed to honoring.

* * * * *

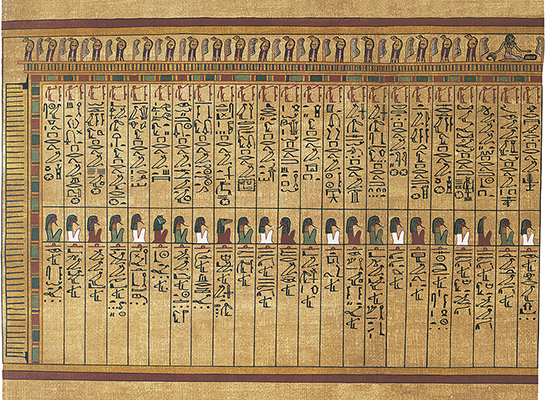

Bill Corsa made the suggestion to display Plates 11 and 31 as gatefold spreads. This allowed for fully framed scenes to be presented in an absolutely coherent and aesthetic manner. The 42-part Negative Confession (shown below), is a source of our own Ten Commandments. Egyptian religion is also the root of our Judeo-Christian belief in the after-death resurrection promised as a reward for righteous living.

Gatefold spread of Plate 31: The Negative Confession. Note the bordered frame of the vignette is kept intact.

(As restored © 1994, 1998 James Wasserman)

* * * * *

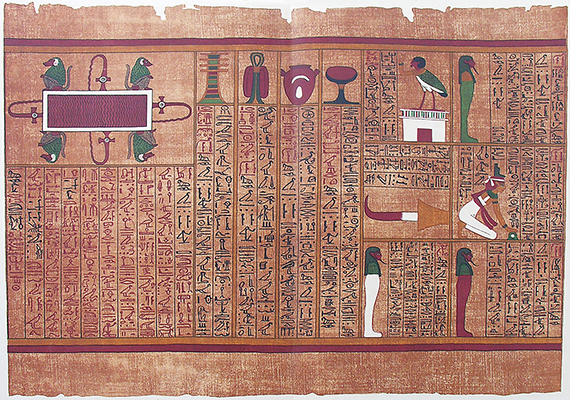

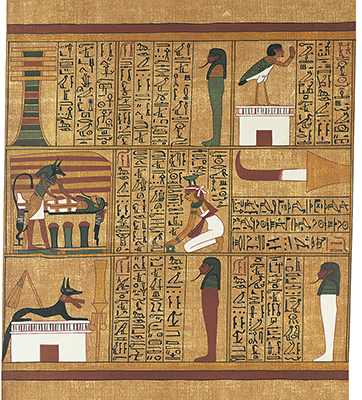

Carol Andrews of the Department of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum (Budge’s old position) threw her full support behind our project when she saw our restoration. She was especially impressed by Plates 32 through 37 which were completely botched by the yardstick method of cutting. Here is a poignant example of the problem with the cutting of the original Papyrus.

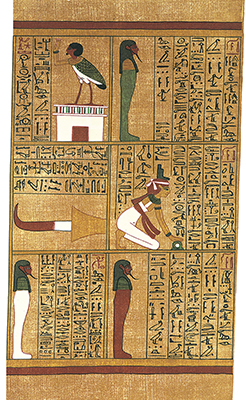

This is Sheet 30 of the Papyrus as cut by Budge. A bordered scene of two columns is shown at right.

Sheet 31 shows the continuation of the bordered scene, three columns, on the left.

Here is the corrected modern Plate 33. Each of the figues is addressing the other.

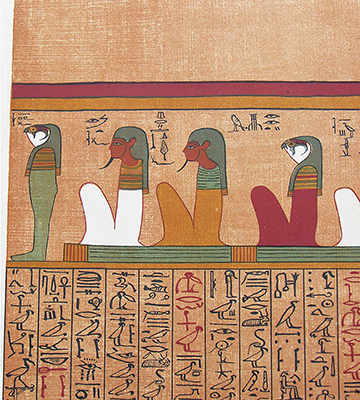

The top row shows the soul of Ani praising Ra at left and right. Two of the Four Sons of

Horus, Hapy and Imsety, address each other on opposite sides of the Djed Pillar in the center.

In the middle row, two Flames are at opposite sides, while Isis and Nepthys kneel at either side of

the embalming performed by Anubis. In the bottom row, the two Shabtis of Ani address each other

at the opposite sides,while the two other Sons of Horus, Qebehsenuef and Duamutef,

address one another on either side of Anubis recumbent on a shrine.

(As restored © 1994, 1998 James Wasserman)

* * * * *

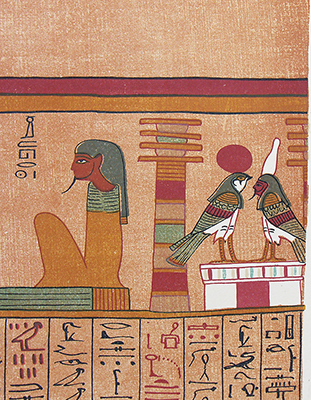

One of my favorite restorations is quite subtle. On our Plate 8, a figure holding an Ankh in each hand is shown emerging from a funerary chest. He is surrounded by the Four Sons of Horus: the ape-headed Hapy, human-headed Imsety, jackal-headed Duamutef, and falcon-headed Qebehsenuef. However, when Budge cut the Papyrus, Qebehsenuef was placed on the left side of Sheet 9 among a group of unrelated deities.

Upper right of Sheet 8 of the Papyrus as cut by Budge.

Three of the Four Sons of Horus. (Facsimile Lithograph)

Upper left of Sheet 9 of the Papyrus as cut by Budge.

Fourth Son stands alone. (Facsimile Lithograph)

Plate 8: Upper right. The Four Sons of Horus

are reunited, as intended by the Scribe.

(As restored © 1994, 1998 James Wasserman).

* * * * *

A particularly complex retouch challenge occured at the upper right of Sheet 9. Because of the intricasies of the original art, Budge wound up cutting the Djed Pillar as shown below. Many hours were spent by Photoshop artist Daniel Herman in carefully displaying that beautiful vignette intact on our Plate 10.

In the upper right of Sheet 9 of the Papyrus, Budge sliced the Djed Pillar on the right. (Facsimile Lithograph)

Upper left of Sheet 10 of the Papyrus, as cut by Budge, shows the rest of the Djed Pillar (Facsimile Lithograph)

Here is the properly restored Plate 10. (© 1994, 1998 James Wasserman)

* * * * *

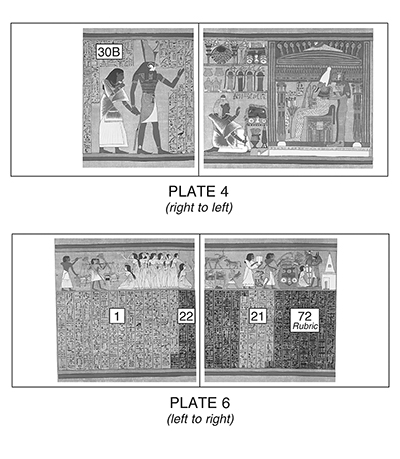

One understated feature of the book is the Map Key to the Papyrus. It is a miniature reproduction of the scroll as composed of the thirty-seven recut plates. It shows the beginning and end of each chapter in shaded sections. Some plates have only one chapter such as Plates 1, 2, 3, and elsewhere. Others, such as Plates 16 and 18, contain as many as 7 or 8 chapters each. We also show the direction in which a specific chapter is written, as hieroglyphics can be read either right-to-left or left-to-right. The Map Key was made possible by Budge’s careful character-by-character delineation of the Papyrus in his 1895 translation.

Four Plates from the Map Key of the Papyrus.

(© 1994, 1998 James Wasserman)

* * * * *

A word on the translation of the Papyrus: Dr. Goelet made clear, first, that Budge’s translation falls far short of modern standards, and second, that the hieroglyphic text of the Ani Papyrus itself is of uneven quality, often much inferior to the excellence of its vignettes. When the Papyrus of Ani was created, the hieroglyphic script was already beginning to fall into disuse. Dr. Goelet proposed we use Dr. Raymond O. Faulkner’s translation of the “ideal text” of each chapter below the images of the Ani Papyrus, supplemented by Goelet’s own translations where necessary. Our text would then represent the best translation from the best Egyptological sources for the specific chapter of the Book of the Dead illustrated in the Ani Papyrus.

People have asked why we did not photograph the original Papyrus of Ani in the British Museum, instead using the 1890 facsimile as our primary artistic reference. The reason is simple and heartbreaking—the damaged condition of the 3500-year-old original. Codices Selecti Volume LXII (Akademische Druck und Verlagsanstalt, Graz, 1979, ed. E. Dondelinger) presents photographs of the original papyrus disfigured by the effects of sunlight and glue. Budge’s facsimile was much closer to what the original would have looked like when it was first created.

The coordination of our three principal scholars—Dr. Goelet, Carol Andrews, and Dr. Eva von Dassow—with constant editing, proofreading, and text correction was formidable. Dr. Goelet’s introduction and extensive commentary were edited by Dr. von Dassow. We also include the balance of the Theban Recension of The Book of the Dead, (the approximately 100 chapters not chosen by Ani and Tutu for inclusion in their personal scroll).

This book corrects the greatest publishing oversight in 3500 years. The Egyptian Book of the Dead is a “gateway book.” It has remained an introduction for generations of Egyptologists. People are drawn to it in a seemingly mysterious way. Yet when they approach it for study, they find themselves among a bewildering array of either overly-technical material, collections of haphazard imagery, or text completely devoid of imagery.

This edition allows both the specialist and non-specialist to share an invaluable resource of antiquity, and experience both the intellectual and mystical dimensions of the original sacred scroll.

I believe the power, wisdom, and spiritual vision offered in the Papyrus of Ani can be greatly beneficial to our modern culture. Perhaps in searching out our spiritual roots, we can rediscover the golden thread all but lost today. The ancient Egyptians offered an altogether refreshing assessment of our inherent human divinity. Were we, as a culture, to be reminded of such an elevated spiritual condition, might not the true pride so engendered help end the irresponsibility endemic to our world?