The Roots of O.T.O. in the Crusades

Published in Solstandet Journal, January, 2018 e.v.

(Adapted from a talk presented at NOTOCON, August 2017 e.v.)

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law

As occultists we regard ourselves as the protectors of and seekers after a Tradition that extends to the mists of time—perhaps even before life on Earth. At the very least, mystics have gazed back thousands of years to the mythical civilizations of prehistory such as Atlantis and Lemuria. And for the more historically-minded, I doubt there is a person reading this who has not imagined him or her self in Ancient Egypt—looking at the pyramids, standing before the Sphinx, deep within a Temple of Initiation.

We share a fascination with the past because we believe there is a thread that extends back through time to fellow seekers who have sought after the same things we do. When did meditation begin? What is the origin of yoga? Where did Magick originate? When did people become aware of the spiritual quest? The answer to these questions is the same: “In Antiquity.”

Crowley’s A\A\ reading list reaches back to some of the oldest literature of humankind. And decade after decade, scholars are gaining greater access to ancient languages and alphabets, and unearthing new finds. Scripture and myth are the most common form of ancient literature and this is true for a very good reason. The search for unity with the Divine is the most important task of all conscious beings. And especially in ancient cultures, only the most conscious could read and write.

Some History of the Mediterranean

We are all familiar with the evolution of spiritual and religious teachings whose roots extend to Mesopotamia and Egypt. The ancient Greeks were as fascinated with Egypt as we are. Egypt held for them the same sense of awe and majesty. Pythagoras—perhaps the greatest spiritual teacher in Western culture—traveled to the temples of Egypt seeking wisdom from the priests and priestesses who held the secrets he sought.

The Mediterranean trade routes of antiquity found people from India and even China interacting with mystics and magicians from Egypt, Persia, Israel, and Greece. As happens to this day, seekers exchanged information and practitioners interacted with each other. Aspirants shared thoughts and techniques across language and cultural barriers about how to unite human consciousness with the promise they intuited of the stellar world beyond the five senses. Such knowledge was fertilized and grew as it was communicated between people of good will.

Mystery schools flourished throughout the ancient world. The best known to us in the West are, of course, the Eleusinian Mysteries. But Pythagoras had an academy, as did Plato, Aristotle, and countless others whose names have blended into time. Schools, monasteries, and communities dotted the landscape of Greece, the Holy Land, and Egypt. The wisdom of the Essenes, Gnostics, and Hermeticists was taught, practiced, and recorded as the centuries passed.

The Decline and Fall of Rome

The evolution from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire, and the development of Christianity, would challenge the free flow of information among such decentralized mystic communities. Rome sought administrative control over its ever expanding territory. Beginning with Emperor Constantine, Rome’s embrace of Christianity in the fourth through sixth centuries led to the suppression of centers of Pagan learning. But the fall of Paganism was also facilitated by its own degeneration, especially in Rome. Corruption and excess contributed to the widespread embrace of the newer faith. It is important to understand that the popularity of Christianity was a symptom, not a cause, of Rome’s decline.

It has been said many times that the fall of Rome lasted longer than the life of many other civilizations. In time, Rome was unable to defend herself against the waves of invasions from the Barbarian tribes of northern Europe. The third to fifth centuries witnessed great social disruption, increasing chaos, political upheavals, and the spread of ravishing diseases. By the end of the fifth century, Rome was no longer in control of the Western Empire.

In the Eastern Empire, the Emperor Justinian closed the Neoplatonic academy in Athens in 529. Scholars, monks, mystics, and anchorites fled East. They were welcomed by the Sassanian dynasty in Persia where they began to reestablish new centers of learning. They shared the foundational teachings of the Western Mystery Tradition with their new hosts, including the works of the Pythagorean school, Aristotle, and Plato, as well as those of Hermeticists and Neoplatonists like Plotinus, Porphyry, Iamblichus, and Proclus. Thus the Hermetic writings lived on—though lost to the West until the 15th century when the manuscripts were returned by way of Byzantium to Florence and translated into Latin by Marsilio Ficino. (The Eastern Roman Empire survived until 1453 when it was overrun by the Ottoman Turks.)

The Dark Ages

With the fall of Rome in the sixth century, however, the period popularly known as the Dark Ages began in the West. Superstition and religion replaced science and philosophy. Medical knowledge was limited to women, Arabs, and Jews. The economy was in collapse. Illiterate peasants faced social conditions akin to slavery. The average lifespan was 30–35 years. Lawlessness prevailed with a constant state of looting and fighting between feudal warlords and their henchmen. Life in the Dark Ages was truly nasty, brutal, and short.

The Church was both a cause and a remedy. While its prohibitions against bathing led even the most wealthy to develop skin disease and infestations by vermin, the Church was the primary civilizing influence among the rude tribes of the north. Although education was confined to males and reading materials limited to scripture, the Church kept language and literacy alive. For all the pernicious doctrines the Church taught of good and evil, the suppression of natural instincts, and the doctrine of Original Sin, it also taught lessons of morality, compassion, charity, service, and duty to the community.

The Rise of Islamic Conquest

As if to add insult to the injury of the Barbarian defeat of Rome, the scourge of Islam burst upon the world stage in the seventh century. Originally confined to Arabia, the thirst for conquest and plunder, and the passion for conversion, caused the new religion to go north and west. Much of Persia and the Mideast fell to Muslim domination.

Jerusalem was conquered in 638, some six years after Muhammad’s death. Muslim armies fanned out around the Mediterranean and entered Asia Minor to the north, and Egypt and North Africa to the south. In the mid-seventh century, Arab naval invaders took Cyprus (652) and Rhodes (655). Eighth century invasions included the conquest of Spain (711 and two unsuccessful invasions of France (732 and 735). In the ninth century Arab armies took Corsica (809), Sardinia (810), Crete (823), Sicily (827), Palermo (831), Messina (843), Malta (870), and Syracuse (878). They attacked Rome in 846 and 849. In 879 Rome began paying an annual tribute for peace.

In 1010, the Muslim destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem (where Christians believe Jesus was crucified and buried) aroused great emotion in Europe. In 1071, the Eastern Roman army was defeated and humiliated at the Battle of Manzikert in modern Turkey. The Byzantine Patriarch Alexus Comnenus begged the assistance of Pope Urban and the West.

The Crusades and the Knights Templar

The First Crusade was accordingly launched in 1095. In 1099 the Crusaders reclaimed Jerusalem. Twenty-three years later, in 1118, the Knights Templar were founded. Hoping that many readers have read (or will read) The Templars and the Assassins, I will not spend a lot of time here discussing the Templars. The Order lasted about two hundred years.

In 1291, the Crusades ended in defeat and the Templars returned to Europe where they were slandered with charges of heresy by political operatives—whose command of the Big Lie and Fake News is unrivalled even in modern times. As Crowley described these events in Concerning the Law of Thelema:

“You recall that the Order of the Temple was only overthrown by a treacherous coup d’état on the part of a King and of a Pope who saw their reactionary, obscurantist, and tyrannical programme menaced by those knights who did not scruple to add the wisdom of the East to their own large interpretation of Christianity, and who represented in that time a movement towards the light of learning and of science . . .”

Arrested in France on Friday the 13th (October 1307), the Order was disbanded by the Pope in 1312. In 1314, Jacques de Molay, the last Templar Grand Master, rescinded his confession made under torture and was burned at the stake while proclaiming the Order’s innocence. He is said to have uttered a curse from the flames against King and Pope, both of whom were dead within the year. Surviving members joined other orders or were pensioned, many having been tortured and many others killed during the seven year persecution in France. The Templars in other European countries were similarly disbanded under orders from the Pope.

The Templars and the O.T.O.

Why are the Knights Templar still so important to us today as members of Ordo Templi Orientis?

Let’s begin with our name. In 1906, Crowley’s predecessor as Outer Head of the Order, Theodore Reuss, published the first version of the Constitution of Ordo Templi Orientis. He described O.T.O. in the following words: “This organization is known at the present time as the: Ancient Order of Oriental Templars. Ordo Templi Orientis.”

He dated his 1906 document “Anno Ordinis 788”—or 788 years after 1118, the year of the founding of the Templar Order in Jerusalem.

When Crowley announced the O.T.O. in September of 1912 in Equinox I, No. 8, he described “. . . the formation of the body known as the ‘ANCIENT ORDER OF ORIENTAL TEMPLARS.’” The announcement was repeated in Equinox Numbers 9 and 10.

In 1919, with the publication of the Manifesto of the O.T.O. in the Blue Equinox, Crowley reiterated our link with the Knights Templar: “The letters O.T.O. represent the words Ordo Templi Orientis (Order of the Temple of the Orient, or Oriental Templars . . .”

In 1944, Grand Master Ramaka (Wilfred T. Smith) went so far as to state in an O.T.O. Prospectus that our Order is descended from the Templars, as founded in 1118, and:

“it has existed in secret right down to the present time. The continuity has been maintained, and the inner secrets have been transmitted to us through an unbroken line of Grand Masters.” [emphasis added]

Freemasonry and the Crusades

While the Rosicrucians literature of the early 17th century made no specific claims to derivation from the crusading military orders, their founder Christian Rosencreutz was said to have traveled widely through the Holy Land in search of wisdom during the 15th century. On his return to Europe, he shared these teachings with the first three Brothers of the Rosy Cross.

Freemasonry publicly announced itself to the world in 1717 with the formation of the United Grand Lodge of England. Soon after, in 1736, Andrew Michael Ramsay—a Scottish Freemason who later became the chancellor of the Grand Lodge of France—introduced the idea of an alliance between the Freemasons and the military orders during the Crusades.

Ramsay described the lineage of Freemasonry in his famous 1736 Oration:

“Some ascribe our institution to Solomon, some to Moses, some to Abraham, some to Noah, and some to Enoch . . . or even to Adam. Without any pretence of denying these origins, I pass on to matters less ancient. . . .

“At the time of the Crusades in Palestine many princes, lords, and citizens associated themselves, and vowed to restore the Temple of the Christians in the Holy Land . . . Some time afterwards our Order formed an intimate union with the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem. . . .

“This union was made after the example set by the Israelites when they erected the second Temple—who, whilst they handled the trowel and mortar with one hand, in the other held the sword and buckler.”

Ramsay hymned the moral qualities of the Crusaders and looked to them for the Masonic values of honor and brotherhood. He wrote:

“What obligations do we not owe to these superior men who, without gross selfish interests, without even listening to the inborn tendency to dominate, imagined such an institution—the sole aim of which is to unite minds and hearts in order to make them better, and form in the course of ages a spiritual empire …”

As if anticipating Crowley’s words in an Open Letter to Those Who May Wish to Join the Order, Ramsay further elucidated upon the idealized culture of the Fraternity:

“Thus the obligations imposed upon you by the Order, are to protect your brothers by your authority, to enlighten them by your knowledge, to edify them by your virtues, to succour them in their necessities, to sacrifice all personal resentment, and to strive after all that may contribute to the peace and unity of society.”

Ramsey proclaimed in his posthumously published Philosophical Principles of Natural and Revealed Religion (1749) that: “Every Mason is a Knight Templar.”

The Templar-Masonic connection is the rationale for the Order of the Temple Degree in the York Rite and the Thirtieth Degree or Knight Kadosch in the Scottish Rite.

The Grail and the O.T.O.

Where else may we find the influence of the Knights Templar and the Crusades in our Order?

The literature of the Grail Tradition surfaced during the Crusades. Chrétien de Troyes, Thomas Mallory, and anonymous others described a mysterious object known as the Holy Grail. Described with some differences in various accounts, the Grail is frequently depicted as held by a group of Priestesses in the Castle of the Mount of Salvation and guarded by armed knights—sometimes specifically identified as Knights Templar.

In the first years of the 13th century, Grail author and knight Wolfram von Eschenbach wrote Parzival. Describing the knights who dwell with the Grail at Munsalvaesche, Eschenbach wrote:

“Always when they ride out, as they often do, it is to seek adventure. They do so for their sins, these Templars, whether their reward be defeat or victory. A valiant host lives there, and I will tell you how they are sustained. They live from a stone of the purest kind. If you do not know it, it shall here be named for you.

“It is called lapis exillis. By the power of that stone the phoenix burns to ashes , but the ashes give him life again. . . . The stone is also called the Grail.”

In perhaps the most telling indicator of the influence of the Crusades and the Grail tradition upon O.T.O., Eschenbach described what would later be illustrated in our Order’s Lamen.

“This very day there comes to [the Grail] a message wherein lies its greatest power. Today is Good Friday and [the Templars] await there a dove, winging down from Heaven. It brings a small white wafer, and leaves it on the stone.”

The Grail is that which nourishes life on Earth, and particularly the lives of its Templar Guardians: “Thus, to the knightly brotherhood, does the power of the Grail give sustenance.”

Christianity and the Spiritual Lineage of O.T.O.

We who embrace the Law of Thelema often miss the fact that there is a significant religious lineage involved in our Order. As I mentioned in the beginning, the Spiritual Tradition is evolving. Its roots must be respected—lest we risk being perceived as either ignorant or bigoted.

Our Order is derived from a Christian Military Order—whose roots are in Judaism, whose roots are in Egypt. Such is the evolution of the Mysteries through the course of time and the changing of the Aeons.

O.H.O. Theodore Reuss wrote the following in the preface to his German translation of Crowley’s Gnostic Mass:

“The Gnostic Templar-Christians (Neo-Christians, Primitive Christians, Neo-Gnostics) do not seek to found a new religion—they only desire to clear away the debris which the reigning pseudo-Christianity of the Church Fathers heaped on the original Christian religion—so that the true ‘Christos’ doctrine and the religion of the original Christians—the Christian Gnostics—will once more come into its own….”

Saint Bernard and the Holy Warrior

This brings us to Bernard of Clairvaux the widely respected Cistercian religious leader, later canonized. He was a passionate supporter of the Templar Order, which enjoyed a meteoric rise to prominence after he sponsored it. Under Bernard’s patronage, the Templars were recognized as an official body of the Catholic Church in 1128.

The model of the Holy Warrior in the West originated with King David. The Bible story of the young boy defeating the champion of Iniquity speaks to the concept of God ordaining the rightness of the warrior’s cause—as long as we are in harmony with the Divine Will or True Will.

The Templars combined the role of medieval knight with that of the vows of a monk. Knight/Monks, they were equally skilled with weapons as they were observant in their religious duties.

Bernard wrote an important letter to the Templars in 1135 called The Book of the Knights of the Temple: In Praise of the New Knighthood. An inspiring discourse, it offered a description and rationale for the Order and the concept of the spiritual warrior.

“It seems that a new Knightly Order has recently been born . . . This new Order of knights is one that is unknown by the ages. They fight two wars, one against adversaries of flesh and blood, and another against a spiritual army of wickedness in the heavens.”

He describes the ethical freedom of the Divine Warrior:

“Truly he is a fearless knight and completely secure. While his body is properly armed . . . his soul is also clothed with the armor of faith. . . . he fears neither demons nor men.”

Bernard further hymns the righteousness of the cause of the warrior-monk, “He does not carry a sword without just cause for he is a minister of God, and he punishes malicious men for the praise of the truth. . . .”

He mocked those secular knights whose affectation and love of luxury, bullying, sexual profligacy, rowdiness, and drunkenness disgusted him:

“You dress your horses with Chinese silks, and decorate your armor with additional rags of which I am ignorant; paint your shields and saddles; cover your bridles and spurs with gold and silver and expensive gems; and then with all this pomp, shamefully and with thoughtless haste rush to your death.

“Are these the ornaments of a Knight, or the trinkets of a woman? Do you think the swords of your enemies will be repelled by your gold, shrink from your jewels, or be incapable of piercing your Chinese silks? . . .”

Bernard contrasted such fopperies with the traits of the Templars:

“How different is the knight of God from the knight of the world? . . . In the first place discipline is not lacking, neither is obedience regarded with contempt. . . . Dedicated all together, they are of one heart and one soul.

“They rival each other in honor; they carry each others burdens. No impractical word, useless work, uncontrolled laughter, or any murmur or whisper is left uncorrected when once perceived.”

When comparing again the Templars with the secular knights of Europe, Bernard injects, perhaps, a touch of humor.

“When readying for imminent battle, their inner faith is their protection. On the exterior, steel not gold is their security — since they are to strike fear in the enemy, not provoke his avariciousness.

“They need to have horses that are swift and strong, not pompous and decorated. Their purpose is fighting, not parades. They seek victory, not glory. They would rather strike terror than impress.”

The following exhortation inspired the Templars in battle for two centuries—sometimes leading to terrible defeats—but never through lack of courage.

“No matter how outnumbered they do not consider the savage barbarians as formidable multitudes. Not that they are secure in their own abilities, but they trust in the virtue of the Lord Sabaoth to bring them to victory…. We have seen one man in hot pursuit put a thousand to flight and two drive away ten thousand.”

Bernard’s words anticipate the later promises of The Book of the Law:

“I will bring you to victory & joy: I will be at your arms in battle & ye shall delight to slay. Success is your proof; courage is your armour; go on, go on, in my strength; & ye shall turn not back for any!“

Bernard spoke of the difficulty of accurately identifying the Templars:

“I do not know if I should address them as monks or as knights; perhaps they should be recognized as both.“

Similarly, in the Manifesto of the O.T.O., Crowley speaks of “the Knight-monks of Thelema.”

Saint Bernard and the Goddess

Bernard was also a passionate devotee of the Virgin Mary—the Christian Nuit. He wrote:

“She, I say, is that shining and brilliant star, so much needed, set in place above life’s great and spacious sea, glittering with merits, all aglow with examples for our imitation. . . . Let not her name leave thy lips, never suffer it to leave thy heart. And that thou mayest more surely obtain the assistance of her prayer, see that thou dost walk in her footsteps.

“With her for guide, thou shalt never go astray; whilst invoking her, thou shalt never lose heart; so long as she is in thy mind, thou shalt not be deceived; whilst she holds thy hand, thou canst not fall; under her protection, thou hast nothing to fear; if she walks before thee, thou shalt not grow weary; if she shows thee favor, thou shalt reach the goal.”

Bernard crafted the Templar Rule which states that the Order is dedicated to the Virgin Mary:

“Our Lady was the beginning of our Order, and in her and in her honour, if we please God, will be the end of our lives, and the end of our Order, whenever God wishes it to be.”

As long as we understand Mary as an archetype of Nuit and Babalon in an earlier Aeon, I think the Templar identification with the Goddess is further proof of our spiritual lineage.

Chivalry and the O.T.O.

The concept of Chivalry is another shared value between the medieval warrior of the Crusades and the modern O.T.O. Chivalry marked the creative high-point of Feudalism. It developed from a combination of French and German military codes, Old Testament battle traditions, Muslim warrior ideals, and Christian devotion.

Protection of the weak, courtesy, truthfulness, defense of the Church, chastity, honor, and courage were all elements of Chivalry. The idealization of the beloved was another. The knight pledged himself to a noble lady to whom his efforts were dedicated. The chivalric idealization of the feminine was a marked departure from the utilitarian impersonality with which women had previously been viewed in Western culture.

Crowley writes in Concerning the Law of Thelema: “The rules of chivalry, and those of Bushido in the East, gave the best chance to develop rulers of the desired type.”

In The Book of Lies, he spoke favorably of the obligations inherent in the behavioral code of Chivalry: “The only solution of the Social Problem is the creation of a class with the true patriarchal feeling, and the manners and obligations of chivalry.”

And in Absinthe: The Green Goddess, he describes the ideal of Chivalry as part of the moral code of the adept: “for in the right conception of this life as an ordeal of chivalry lies the foundation of every perfection of philosophy.”

A difference between the Chivalry of the Middle Ages and the Chivalry of the New Aeon may be best illustrated by The Book of the Law: “Let the woman be girt with a sword before me.” For women too will be warriors in the battles of the New Aeon. The Book of the Law proclaims: “Every man and every woman is a star.” Women are then equally empowered and equally responsible in this knightly ordeal.

O.T.O. as a Military Order

Everywhere we look in O.T.O. we find military iconography and language—from our magical weapons such as the Lance, Sword, and Dagger, to our hierarchical structure of leadership.

In An Intimation with Reference to the Constitution of the Order Crowley imagines a hierarchy in which he describes the Sixth Degree as a military body “vowed to enforce the decisions of authority.” He calls the Seventh Degree “the Great General Staff of the Army of the Sixth Degree.”

The Mysteries were often the provenance of soldiers. Yoga is said to give been developed by the Kshatriya caste of Indian warriors. Crowley mentioned the doctrine of Bushido exemplified by the Japanese warrior priests. The shamanistic Norseman embraced Valhalla with certainty, not faith The cult of Mithras flourished almost exclusively within the Roman army. Soldiers travel widely, share in alien cultures, and are regularly confronted by the possibility of their own deaths.

We recall in the Buddhist teachings that young Prince Siddhartha was guarded from the awareness of suffering by an elaborate palace garden erected by his father. When Siddhartha ventured past the fantasy palace gates and confronted old age, sickness, and death for the first time, he understood the First Noble Truth: All is Suffering. He was set firmly on the Path of Enlightenment and Buddhahood. Who better to understand human suffering than the soldier?

I celebrate the vision of O.T.O. as a body of warriors committed to the martial values of courage, integrity, loyalty, bravery, cunning, and chivalry. Ours is the duty to protect the weak and battle the wicked. We are to count our years by our scars. We are to be dangerous. This is, after all, the Aeon of Horus.

The Teaching of the O.T.O.

We are introduced to the Order in a ceremony in which we are instructed in a series of behaviors that will guide our progress throughout the rest of our career. These principles include the chivalric and knightly moral, ethical, and behavioral values that have been highlighted throughout this paper.

Crowley makes clear throughout the rituals of initiation that O.T.O. is fighting a spiritual war against evil while waging a political war in the name of Liberty. I remind you of St. Bernard’s words to the Templars 900 years ago. “They fight two wars, one against adversaries of flesh and blood, and another against a spiritual army of wickedness in the heavens.”

Today’s Knight/Monks of Thelema practice Yoga and Meditation to enhance our Magick. Crowley knew we would face great periods of dryness. That initiates would need grit and determination, steadfastness and perseverance in the face of repeated failure and difficulty. He understood that discipline is the means by which we would fulfill our oath of attainment—to build the Temple wherein we shall offer habitation to the Divine within our own bodies.

The O.T.O. and the Assassins

As noted earlier, the Templars were accused of heresy by the power structure of Europe to which they returned in defeat. Among the charges brought against them was collusion with the enemy and the embrace of antinomian blasphemies against Christianity. In my just-published novel Templar Heresy, I have taken each of the slanders made against the Order and advanced the idea that an elite group of Templars were actually guilty of a variation of such charges. These revolutionaries overturned a thousand years of Christian tradition with their embrace of Gnosticism—which I define as the personal knowledge of God within the human body.

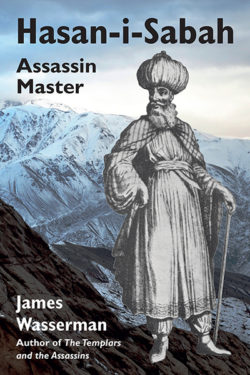

I focus especially on the influence of the Qiyama doctrine of the Assassins (Nizari Ismailis) in the development of the Templar Gnosis. The Qiyama essentially proclaimed, “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law” for the first time, shattering the Muslim world by standing Sharia Law on its head. Hasan II ala dhikrhi as salam (upon whose mention be peace) proclaimed the immanence of Gnosis, the transition of the Nizari Ismaili community to full enlightenment, the presence of God on earth in the here and now. He transformed the Nizaris by preaching their freedom to abandon outside rituals of traditional religious observance in favor of the appreciation and enjoyment of the state of transcendence he announced. Gone were the Ramadan fast, the Five Pillars of Islam, the centrality of Mecca, and the stifling conformity of orthodox collectivism. The Qiyama proclaimed that all the earth was illumined by the radiance of Allah, that “Nothing is true, everything is permitted” to one who is doing his True Will.

Among the Christians, the medieval French Cathars of the Languedoc similarly rejected the doctrines of the Catholic Church. I believe their teachings were another central influence in the heresies imputed against the Templars. Cathars denied the Crucifixion. They regarded Jesus as an angel sent by God in His love for mankind to teach us the means of attainment. They despised the Cross as an instrument of torture. They completely rejected the authority of the Church, the pope, and the clergy. They consecrated women in full equality as their own clergy and preached a life of material simplicity, vegetarian diet, and (sadly) a rejection of sexuality and procreation.

Crowley merely touches on the Assassin Order in the most superficial way in his writings. Yet, we know he was aware of the Assassin legend and Hasan-i-Sabah, the founder of the Order. Crowley had translated Baudelaire’s Poem of Hashish as a part of The Herb Dangerous, a series that ran in the first four numbers of The Equinox. Baudelaire mentions accounts of the Assassins by Marco Polo, Joseph Von Hammer-Purgstall, and Silvestre de Sacy. Von-Hammer’s important History of the Assassins had been translated into English by Crowley’s time. Thomas Keightley’s excellent book Secret Societies of the Middle Ages was also available to him. I have no idea why Crowley never went deeper into the Assassins—nor why they have a singular obsession of mine for decades.

I suggest that Hasan II is a fitting embodiment of the archetype of Baphomet, the Grand Master of O.T.O. Crowley publicly identified himself as Baphomet and proclaimed Baphomet the god of the Templars. Hasan II’s chief disciple, Rashid al-Din Sinan, was a Syrian Assassin king known to have interacted with the Knights Templar. Sinan was a true heretic. He was a proponent of the Qiyama, a Gnostic, and a Magician who preached the overturning of outmoded religious beliefs and the presence of the Divine on Earth. You will find him well worth your time to investigate.

Living Life in the Order

In closing, we of O.T.O. have inherited a vibrant spiritual tradition that includes the celebration of honor, integrity, courage, self-reliance, and the warrior’s creed of loyalty and discipline as the basis of our ethical teachings. Rebellion is also part of that picture—as is the need for hierarchical obedience. All contradictions being resolved above the Abyss, we accept ambiguity as complementary with our three-dimensional experience and rejoice in its challenges.

I have just two pieces of advice if you are a member of O.T.O: Never lose your sense of humor . . . and never let the bastards get you down!

Love is the law, love under will.

James Wasserman has been an active member of O.T.O. since 1976. He is the founder of TAHUTI Lodge in New York City and the author of The Templars and the Assassins: The Militia of Heaven; An Illustrated History of the Knights Templar; and Templar Heresy: A Story of Gnostic Illumination. He is currently working on a biography of Hasan-i-Sabah, to be published by Ibis Press.